The Dmanisi Hominids/Hominins

The Georgian word patara (პატარა) could be translated as tiny, small, or little. Patara Dmanisi, or the Little Dmanisi, is the name of the village or location where the Dmanisi hominids (hominins) in the present-day country of Georgia were discovered.

Unlike Lucy’s, the Dmanisi fieldwork site is not in remote badlands. It is located some 85 km southwest of Tbilisi, the capital city of the country.

It is located where the Mashavera and Pinezauri rivers cut canyon- like gorges in basaltic lava, resulting in the formation of an elongated cape – basaltic plateau of triangular shape.

The Damanisi site is a sacred or venerated place in a few different yet connected ways. It is a place of paleoanthropological fieldwork as well as education. It is also a small museum and a nature reserve.

Besides the paleolithic or paleoanthropological Dmanisi, there is also an archaeological Dmanisi.

There is a bronze age Dmanisi.

But, it is the medieval Dmanisi that is an important place and era in terms of the Georgian national religion (The Georgian Orthodox Church). This is particularly because of the Dmanisi Sioni Church (originally built in the fifth century, but remodeled in the 12th century).

With its archaeological fort of the middle ages, Dmanisi also plays an important place in the nationalist historiographical narrative of the Georgian “Golden Age.” In the “Middle Ages,” sometime between the sixth and fourteenth centuries, a strategically and economically important city was built on the Dmanisi plateau, and connected to the network of routes known today as the Silk Road.

It is a representational juxtaposition and intermingling of communal identities (Georgian national and religious, European, Eurasian, Human), of times (paleolithic, bronze age, medieval, and modern), and of places (Georgia’s Dmanisi in relation to Africa, Europe, Eurasia, and Asia), that makes Dmanisi a sacred and significant place.

Archeological excavations in Dmanisi beganon the initiative of Ivan Javakhishvili in 1936.

Ivane Javakhishvili was born in Georgia under the rule of Imperial Russia. He was an eminent scholar of Geogian history and part of the group of intellectuals who promoted Geogian nationalism. He graduated from the Faculty of Oriental Studies of the St. Petersburg University in 1899. From 1901 to 1902, he was a visiting scholar at the University of Berlin. The first volumes of Javakhishvili’s monumental “A History of the Georgian Nation” appeared between 1908 and 1914.

Early in 1918, he was instrumental in founding Georgia’s first regular university in Tbilisi, thus realizing a long-time dream of Georgian intellectuals. He became the head of the Department of the History of Georgia, and later the rector. He was forced to step down in 1938, when the Stalin eara’s purges were in force, but was soon appointed director of the Department of History at the State Museum of Georgia which he headed until his death in Tbilisi in 1940.

Dmanisi major paleoanthropological discoveries in their historical context, as well as in relation to different ideas pertaining to movement, size, and placement.

There is a history to paleoanthropological Dmanisi discoveries, of how over years more material remains have been revealed.

There is also a history of representing the Dmanisi bodily remains and their importance, in terms of their movement, size, and placement, to the public, as well to the scientific community.

Movement

By movement I mean the “Out-of-Africa” exedus to Dmanisi/Georgia.

Size

By size I am referring various sizes related to the of Dmanisi fossilized bodies. Size plays an important role in the “Out-of-Africa” section of the Dmanisi narrative, as well as in terms of placement, in the second sense below.

Placement

I am pointing to two kinds of placement.

(1) Placement on the continental geographical map. I mean placement of Dmanisi (Georgia) as part of the continental terrains of Europe, Asia, or Eurasia.

Eurasia

“for our purposes here, eurasia is defined broadly as extending from eastern europe, asia minor, and the caucasus in the west to the mongolian steppe, china, and the Korean Peninsula in the east. The vagueness of this definition is intentional as we are less concerned with delimiting the boundaries of the continent than in promoting an inclusive understanding of the region that resists balkanization into small insular research areas. Thus, although the archaeological cases examined in this volume are separated by sizeable distances, much more is achieved by setting them in conversation with one another than by segmenting them into discrete zones. This is not to say that there are not important local traditions that shape archaeological priorities in smaller regions such as the caucasus, central asia, or the russian steppe. yet a central conceit of this and other recent works (e.g., anthony 2007; hanks and linduff 2009; Kohl 2007b; Kuz’mina 2008) is that a broad, integrated archaeology of eurasia is much more than the sum of its parts.”

Source:

IntroductIon: regImes, revolutIons, and the materIalIty of Power In eurasIan archaeology Charles W. Hartley, G. Bike Yazıcıoğlu, and Adam T. Smith

(2) Placement on the human evolution genealogical diagram. I meanplacement of Dmanisi fossils in relation to other hominids/hominins in the human evolution tree diagram.

As we will see, placement of Dmanisi bodies on the continental map, and on the geneaological tree, has been diverse, and has changed over time.

The Damanisi paleoanthropological internet site, a National Museum of Georgia public information venue, lists the major paleoanthropological discoveries in Dmanisi.

Discussion of Dmanisi major paleoanthropological discoveries in their historical context, as well as in relation to different ideas pertaining to movement, size, and placement.

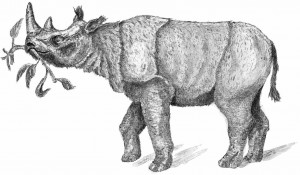

1983 A tooth of a Plio-Pleistocene rhinoceros was discovered unexpectedly.

Its importance was its double “displacement.”

a) Researchers were doing medieval archaelogy fieldwork, but, by chance, they encountered paleonthological evidence. It was a fossilized evidence that was stratigrafically speaking,”displaced”, we might say.

Placement in different layers of an archaeological site is associated with placement in different time periods.

b) There was also a “continental dispalcement.” The tooth had an “African” resemblance, a similarity that, interestingly, later led to the idea of Dmanisi’s role in the Out-of-Africa idea in the human evolution narrative.

Africa/Out-of-Africa framework – Important in the human evolution narrative and debates

Abesalom Vekua and David Lordkipanidze, as Georgian scientists who were involved in the Dmanisi paleoanthropological discoveries when it began, offer their narrative of the early Dmanisi discoveries,in an article titled “Dmanisi (Georgia) – Site of Discovery of the Oldest Hominid in Eurasia” in the Georgian National Academy of Sciences’s Bulletin.

“In 1982 at one of the sectors of the site archeologists came across pits, cut in compact sandy clay, the depth of which was about 3 m, diameter 2-2.5 m. Archeologists supposed that they were intended for economic needs and were dug by the inhabitants of the Middle Ages. After cleaning them, numerous bones of fossilized animals were found on the walls and bottom of the pits. The Paleobiological Institute of the Academy of Sciences was immediately informed about it. It was impossible to ignore such interesting news and we visited Dmanisi the following day. As a result of a detailed study of the pits and bones, we came to the conclusion that we were dealing in this case with the location of quite interesting and varied fossil fauna, whose geological age was possibly much earlier than a million years. Systematic excavations of the Dmanisi paleontological site commenced in 1983, and, owing to periodical financial problems, lasted down to 1991.”

Prof. A.Vekua identified the tooth as belonging to rhinoceros Dicerorhinus etruscus etruscus, a species that is typical for the Early Pleistocene age.

Dmanisi paleoanthropological discoveries started in the 1980s, during the Soviet times, and in the framework of the Georgian State Academy of Sciences. Later, after the collapse of the Soveit Union and the re-emergence of the Georgian modern nation state, the discovery, study, and representations became internationalised or globalised.

In 1982 at one of the sectors of the site archeologists came across pits, cut in compact sandy clay, the depth of which was about 3 m, diameter 2-2.5 m. Archeologists supposed that they were intended for economic needs and were dug by the inhabitants of the Middle Ages. After cleaning them, numerous bones of fossilized animals were found on the walls and bottom of the pits. The Paleobiological Institute of the Academy of Sciences was immediately informed about it. It was impossible to ignore such interesting news and we visited Dmanisi the following day. As a result of a detailed study of the pits and bones, we came to the conclusion that we were dealing in this case with the location of quite interesting and varied fossil fauna, whose geological age was possibly much earlier than a million years. Systematic excavations of the Dmanisi paleontological site commenced in 1983 [3] and, owing to periodical financial problems, lasted down to 1991. A large amount of paleontological fossil material was gathered during this period and, which was more important, In specialists’ opinion, the stone tools found in Dmanisi essentially differ in terms of their archaism from those found to date in the South Caucasus and no analogy has been found on the territory of Eastern Europe. Hundreds of primitive stone tools, remains of fossil animals of more than thousand names were found in Dmanisi; from the Upper Pliocene to the Lower Pleistocene the age of these remains is confirmed biostratigraphically [4, 5]. According to paleontological material, it was demonstrated that the following animals – tortoise, lizard, hare, hamster, wolf, Etruscan bear, spotted jackal, saber- toothed tiger, jaguar, southern elephant, rhinoceros, Stenon horse, giraffe, giant deer, fossil cow, fallow deer, giant ostrich and others – inhabited Dmanisi area and its vicinity in the period of fossilization of fauna.

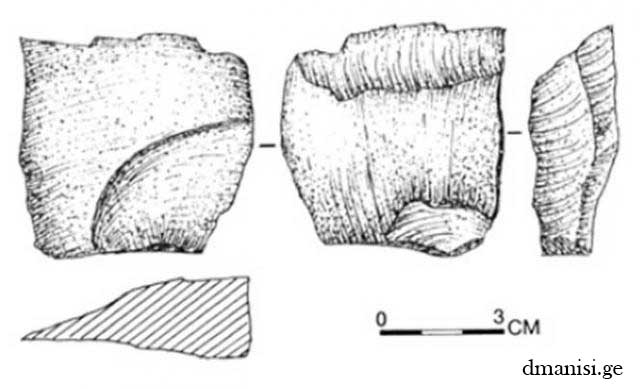

1984 – The first stone tools, indicating that Dmanisi is one of the oldest places of human occupation.

The archaism of the technique of their manufacture caused no doubt; later it was confirmed by well-known specialists of the Old Stone Age Professor D. Tushabramishvili and the German Professor G. Bosinski.

These tools also are used in the Out-of-Africa frame of reference.

1991 – Mandible D211. This first hominin remain opened the debate about to the first human dispersal out of Africa.

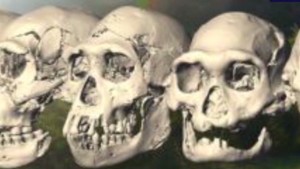

1999 – Two hominin crania – D2280, D2282. These finds demonstrate that Dmanisi hominins are the oldest humans outside of Africa.

2000 – Mandible D2600, raising the possibility of two different species at Dmanisi at the same time.

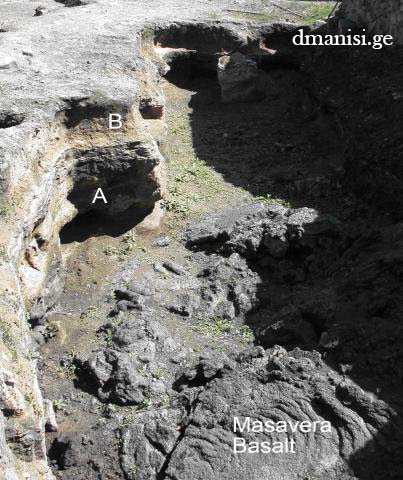

2000 – Absolute dating. Uneroded basaltic lava under site is securely dated to 1.85 million years ago.

2002/2003 – Toothless hominin cranium and mandible – D3444 and D3900. This individual lived several years before death after having lost its teeth. Its condition suggests it could only eat soft plants and animal foods with the help of other individuals.

2003 – The first stone tool cutmarks were found on animal bone.

2005 – Cranium D4500. Discovery of the fifth, most complete cranium of Plio-Pleostocene Homo.

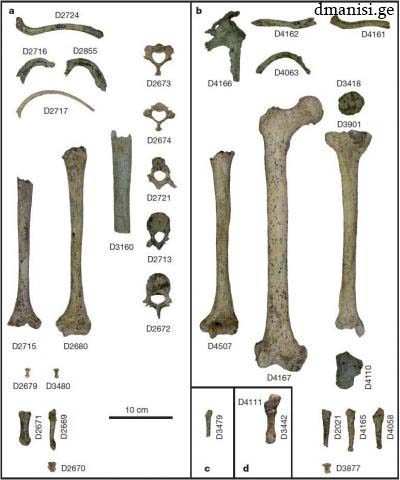

2007 – Postcranial remains of four individuals, partly associated with crania found earlier.

2011 – Earliest human occupations at Dmanisi (1.85 Ma), before the accumulation of the hominin fossil assemblage (1.77 Ma).

2013 – Publication of Skull 5 (D4500 cranium & D2600 mandible) in Sciecne magazine.

———————————-

Now let’s review the above discoveries in their historical context, as well as different ideas pertaining to movement, size, and placement.

1983 a tooth of a Plio-Pleistocene rhinoceros was discovered. Its importance was its double “displacement.” Researchers were doing archaelogical work, but they suddently encountered paleonthological evidence. So, it was “displaced” stratifgrafically speaking, we might say. It had an African resemblance, that, interestingly, led to the Dmanisi’s role in the Out-of-Africa narrative.

1984 – First stone tools, indicating that Dmanisi is one of the oldest places of human occupation. This is an important facet or human evolution narrative, pointing to humans as tool makers.

1991 – Mandible D211. This first hominid remain opened the debate about to the first human dispersal out of Africa. This is an important date in terms of discovery (reappearance) of the (skeletal remains of) Dmanisi hominids, it is also an important date in terms of reemergence of the modern Georgian nation, after its domination and inclusion in the Soviet Union shortly after its genesis during the turn of the twentieth century.

1999 – Two hominin crania – D2280, D2282. These finds demonstrate that Dmanisi hominins are the oldest humans outside of Africa.

2000 – Mandible D2600, raising the possibility of two different species at Dmanisi at the same time.

2000 – Absolute dating. Uneroded basaltic lava under site is securely dated to 1.85 million years ago.

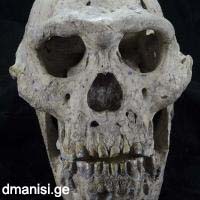

2004 – Toothless hominin cranium and mandible – D3444 and D3900. This individual lived several years before death after having lost its teeth. Its condition suggests it could only eat soft plants and animal foods with the help of other individuals.

Old timer

D3444 – Skull 4 – Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History

Human Evolution Evidence –

http://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/human-fossils/fossils/d3444

This elderly male belonged to a population of Homo erectus that spread from Africa to the Caucasus Mountains in western Asia. Most of his teeth fell out long before he died, and his jaw deteriorated as a result. Members of his social group must have taken care of him. This is some of the earliest known evidence for this kind of group care and compassion in the human fossil record.

————————–

2007 – Postcranial remains of four individuals, partly associated with crania found earlier. ——————–

—————————————

Importance of the Dmanisi hominids lies in the role the play in the out-of-Africa segment of the hominids evolution narrative. Arguing about this out-of-Africa

——————–

David Lordkipanidze is the first General Director of the Georgian National Museum, founded in 2004 and unified 10 major museums and 2 research institutes. Since then the Museum has gradually been transformed from a Soviet-type institution into a vibrant space for culture, education and science.

Most recently, Lordkipanidze was involved in the discovery of ancient hominid remains in Dmanisi. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ro73S3PdF3E

——————————————–

David Lordkipanidze is the head of the Georgian National Museum, and the Head of the Dmanisi excavation project. He and his international and multi-disciplinary team of colleagues, who have been working in Dmanisi paleolithic site for years.

Lordkipanidze with Zezva and Mzia, reconstructions of Palaeolithic Dmanisi man and woman. Tbilisi, Georgia

——————————-

This is how the Dmanisi site is advertised on the Georgian National Museum’s website:

“Homeland of First Europeans

Get closer to science and visit the Dmanisi Museum-Reserve,85 km to the southwest of Tbilisi-a unique place featuring stunning discoveries that are rewriting human history and transforming our view of human evolution. Recent finds in Dmanisi represent the oldest evidence of humans discovered outside of Africa, dating back 1.8 million years. Comprising both the ruins of a medieval city and the prehistoric archaeological site, visitors can enjoy guided tours of the picturesque fortress and ruins that cover the ancient deposits, and watch archaeologists excavate new discoveries.“

There is a plan for expanding the site by building “a 2,000-square-metre dome of steel and glass, which would also extend the number of months each year in which fieldwork can continue. The dome will house an on-site laboratory to analyse the finds and an on-site museum for the growing stream of visitors.”

——————————————–

———-

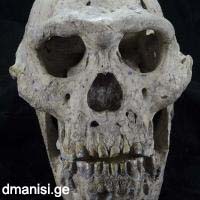

Skull 3

———-

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/2082622.stm

Skull 3 published in Science:

July 2002 – BBC Online, Science/Nature site:

Skull 3, not just the size of the body is small, but also the brain size is small.

Skull 3 First humans ‘small brained’

First footsteps

The new fossil shows how primitive early humans were in their small brain size and great physical variation, says Professor Chris Stringer, head of human origins at London’s Natural History Museum was also interviewed for this report. For him

“The new skull showed clear resemblances to the smaller-sized group of fossils attributed to Homo habilis from East Africa. This might well provide a clue to the ancestry of the Dmanisi humans. Their small brain sizes and primitive technology suggest that the first exodus of humans from Africa around two million years ago did not necessarily require special new adaptations or evolutionary changes but may have related more to extensions of African habitats into western Asia. Perhaps these early humans initially underwent range expansions in African-like environments that were rather familiar to them, rather than making pioneering moves into the unknown.”

———————-

National Geographic

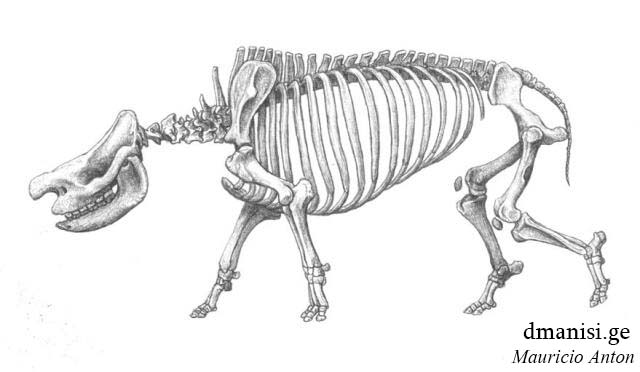

Size Matters Photograph by Kenneth Garrett The discovery at Dmanisi of a Homo erectus thighbone and tibia (shown end to end below a modern human thighbone) allows scientists to estimate the height of this hominin—about four feet seven inches (one meter eighteen centimeters) tall. The thickness of the bones reveals that these early humans spent a lot of time hiking the surrounding Caucasus Mountains. “This individual wasn’t large,” observes scientist Martha Tappen, “but got lots of exercise.” ————

Characterizing the Dmanisi hominids as small in size while narrating them is also evident in a ritual-like event with an international online audience, a TEDx talk in Tbilisi (2011), by David Lordkipanidze. In this narrative the focus is presenting the Dmanisi skull to giants of the human evolution scientific community from a small emerging country, during an international ritual-like gathering of scientists, a conference. Towards the end of his talk, at 12:09, he states that the Dmanisi hominid “was short” (compared to the then prevailing view about the size of the early Homo), “less than one meter fifty centimeters,” and an image of a Dmanisi skeleton is shown, and next to it it says “height 140-150 cm.” http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dC0gdpVS4uM Home georgionous – the first Europeans David’s article in out of Africa book – collection of articles Out of Africa because of “culture” (tools – ) David that Hominin the Dmanisi probably arrived in the region before the Dmanisi folks – based on their tools – based on their bodies, but based on primitive tools (like African) that were made by the so called small bodies But why call them out-of-Africa – if the tools and the fauna and flora that they lived in was similar to similar populations in the so-called (or now-called) Africa.

SIGNIFICANCE OF DMANISI

artistic reconstruction of hominids This is how David talks about the Dmanisi fossils in his different experts “We all come from Africa.

.

.

Questions: When they left africa, and start colonize rest of the world when, who, why Before Dmanisi finds Scientists thought that those who left Africa looked like us, that is they have bigger body size, more advanced advanced tools than earlier Hominids, like Lucy. But a skull from one tiny spot in Georgia, a little country. Dmanisi was an important trade and political center during the middle ages, and a site for archaeological excavations for that period. One day a strange bone of rhinoseours was found, in medieval georgia (different time and place) large team – big international and interdisciplinary team the narrative was that humans left africa about 1,0000 and where bigger environment – giffafs and autriches – typical african environment 15:27 1.8 may tools – very early finds from Africa 1991 – last day of excavation first human bone (jaw) challenged the prevailing views with late Gabunia

Frankfurt 100 yrs birthday of Pitocatonporuos relative of pitocantropous a conference of big names their jaws dropping when they saw our mandible gergia coming to the stage of paleoanthropology and the new jaw creation of devil skull creation of god – small brain 600 cc many primitive features – connected with early Afircan Best collection in the world for this time period who when and why left questions challenged small,

Cradle of first Europeans who were these people toothless sick at least 2 years sick no teeth – may be human behavior and compassion — only 7 percent of the site dmanisi belongs –

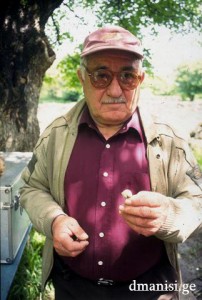

protectt heritage and respect nature every year more and more is found scion belogs to people – make it accessible to the public – for students around th world too new generation in our field new evidence about human evolution of Africa ————————————————-  Lordkipanidze on site at Dmanisi holding mouldings of jaw D2735 and skull D2700 found in 2001.

Lordkipanidze on site at Dmanisi holding mouldings of jaw D2735 and skull D2700 found in 2001.

Africa – Large continent, various ecological zones – why dispersal in Africa is not regarded as important as out-of-Africa movement? Africa – has its own changing ideological connotations in the colonial practices, and in scientific practices dealing with African topics. ————– , describe the

Dmanisi hominids as short or small in size. In a 2007 article published in the Nature, for instance, they characterized the Dmanisi hominids as small in body size. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v449/n7160/full/nature06134.html “The Plio-Pleistocene site of Dmanisi, Georgia, has yielded a rich fossil and archaeological record documenting an early presence of the genus Homo outside Africa. Although the craniomandibular morphology of early Homo is well known as a result of finds from Dmanisi and African localities, data about its postcranial morphology are still relatively scarce. Here we describe newly excavated postcranial material from Dmanisi comprising a partial skeleton of an adolescent individual, associated with skull D2700/D2735, and the remains from three adult individuals.

This material shows that the postcranial anatomy of the Dmanisi hominins has a surprising mosaic of primitive and derived features. The primitive features includea small body size, a low encephalization quotient and absence of humeral torsion; the derived features include modern-human-like body proportions and lower limb morphology indicative of the capability for long-distance travel. Thus, the earliest known hominins to have lived outside of Africa in the temperate zones of Eurasia did not yet display the full set of derived skeletal features.” “The inferred body mass of the large adult individual is between 47.6 kg and 50.0 kg. The body mass of the small adult individual is 40.2 kg. The body mass of the subadult is between 40.0 kg and 42.5 kg.” “Stature estimates for the subadult Dmanisi individual is between 144.9 cm and 161.4 cm. Stature estimates for the large adult individual is in a range of 146.6 cm – 166.2 cm.” (Lordkipanidze et al. 2007:S14). —————————————–

Skull Four

2006 A Fourth Hominin Skull From Dmanisi, Georgia https://apps.cla.umn.edu/directory/items/…/295509.pdf DAVID LORDKIPANIDZE,1* ABESALOM VEKUA,1,2 REID FERRING,3 G. PHILIP RIGHTMIRE,4,5 CHRISTOPH P.E. ZOLLIKOFER,6 MARCIA S. PONCE DE LEO ́ N,6 JORDI AGUSTI,7 GOCHA KILADZE,1 ALEXANDER MOUSKHELISHVILI,1 MEDEA NIORADZE,8 AND MARTHA TAPPEN ABSTRACT Newly discovered Homo remains, stone artifacts, and animal fossils from Dmanisi, Republic of Georgia, provide a basis for better understand- ing patterns of hominin evolution and behavior in Eurasia ca. 1.77 mil- lion years ago. Here we describe a fourth skull that is nearly complete, lacking all but one of its teeth at the time of death. Both the maxillae and the mandible exhibit extensive bone loss due to resorption. This indi- vidual is similar to others from the site but supplies information about variation in brain size and craniofacial anatomy within the Dmanisi paleodeme. Although this assemblage presents numerous primitive characters, the Dmanisi skulls are best accommodated within the species H. erectus. On anatomical grounds, it is argued that the relatively small- brained and lightly built Dmanisi hominins may be ancestral to African and Far Eastern branches of H. erectus showing more derived morphology.

Exedus Out of Africa

Though, for instance, this article points that the emphasis should be on populations, rather than species, and ecological zones, rather than continents, still the constructions Africa and Out-of-Africa are dominant in tangling the issue of hominin evolution.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK208100/figure/mmm00002/?report=objectonly

“In any discussion of hominin dispersal it is possible, and important, to examine the event at many different scales. This paper examines the initial dispersal out of Africa at the scale of populations rather than species, looks at dispersal between ecological zones rather than continents, and considers dispersal within Africa prior to any dispersal out of Africa. Before hominins could disperse out of Africa they needed to disperse out of their likely area of endemism in sub-Saharan Africa to North Africa, the most likely departure point for Eurasia. Prior to the Middle Pleistocene, successful long term colonizations of North Africa by hominins were very rare, and apparently less successful than their colonizations of Eurasia. The Early Pleistocene hominin dispersal into Eurasia was most probably along the western coast of the Red Sea. The ability of hominins to successfully disperse into Eurasia and successfully colonize northern continents was made possible by the ecological and climatic diversity within Africa.”Chapter 3 Saharan Corridors and Their Role in the Evolutionary Geography of ‘Out of Africa I’ Marta Mirazón Lahr http://www.human-evol.cam.ac.uk/desertpasts/pdf/evol_geogra_hum_disp/lahr_2010_out_of_africa_1_bk_chapter.pdf ——————

Dmanisi – crossroad of Africa, Asia, and Europe, place of the first hominin dispersal out of Africa.

Discoveries of Homo remains, including several crania and mandibles with numerous post-cranial remains all dated to ca. 1.77 million years, have reopened the debate about the first human dispersal from Africa. The human fossils found at Dmanisi are the oldest outside Africa by more than half a million years. Before the Dmanisi discoveries, it was thought that the first migrants should have been quite tall, big-brained, and having well-developed stone tools, otherwise, they would not be able to survive out of Africa. However, the Dmanisi hominins contradicted these assumptions: they were physically small, and had small brains. Also, these pioneers were armed with primitive stone tools, and thus did not possess the well-developed tool-making techniques researchers had expected. Among the Dmanisi fossils is the skull and jaw of a toothless old adult. This individual could only survive by eating food that did not require heavy chewing, such as soft plants and animal foods, or by virtue of help from other individuals. The Dmanisi hominins exhibit numerous archaic physical characteristics, typical of early African hominins, but they also share certain similarities with later Homo erectus. It is possible that they could be the ancestors of both the African and Asian branches of Homo erectus. In addition to providing fossil material from several individuals, Dmanisi presents a unique opportunity for paleoanthropologists to study a population of different generations – subadult, adult and old adult. Overall, Dmanisi is a remarkable site, preserving not only one of the most important Paleolithic occupations of Eurasia, but also a rich archaeological record of Georgia’s Medieval period. Importance of the Dmanisi hominids lies in the role the play in the out-of-Africa segment of the hominids evolution narrative. Arguing about this out-of-Africa David Lordkipanidze is the head of the Georgian National Museum, and the Head of the Dmanisi excavation project. He and his international and multi-disciplinary team of colleagues, who have been working in Dmanisi for years, describe the Dmanisi hominids as short or small in size

—————-

Size, Post-cranial, out of Africa. Eurasia, temporate

In a 2007article published in the Nature, for instance, they characterized the Dmanisi hominids as small in body size. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v449/n7160/full/nature06134.html

Postcranial evidence from early Homo from Dmanisi, Georgia

Nature 449, 305-310 (20 September 2007) | doi:10.1038/nature06134; Received 16 April 2007; Accepted 30 July 2007

Postcranial evidence from early Homo from Dmanisi, Georgia

David Lordkipanidze1, Tea Jashashvili1,2, Abesalom Vekua1, Marcia S. Ponce de León2, Christoph P. E. Zollikofer2, G. Philip Rightmire3, Herman Pontzer4, Reid Ferring5, Oriol Oms6, Martha Tappen7, Maia Bukhsianidze1, Jordi Agusti8, Ralf Kahlke9, Gocha Kiladze1, Bienvenido Martinez-Navarro8, Alexander Mouskhelishvili1, Medea Nioradze10 & Lorenzo Rook11

Georgian National Museum, 0105 Tbilisi, Georgia

Anthropologisches Institut, Universität Zürich, 8057 Zürich, Switzerland

Department of Anthropology, Peabody Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138, USA

Department of Anthropology, Washington University, St Louis, Missouri 63130, USA

Department of Geography, University of North Texas, Denton, Texas 76203, USA

Departament de Geologia, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 08193 Bellaterra, Spain

Department of Anthropology, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55455, USA

ICREA, Institute of Human Paleoecology, University Rovira i Virgili, 43005 Tarragona, Spain

Senckenberg Research Institute, 99423 Weimar, Germany

Othar Lordkipanidze Center for Archaeological Research, 0102 Tbilisi, Georgia

Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Università di Firenze, 50121 Firenze, Italy

Correspondence to: David Lordkipanidze1 Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to D.L. (Email: dlordkipanidze@museum.ge).

The Plio-Pleistocene site of Dmanisi, Georgia, has yielded a rich fossil and archaeological record documenting an early presence of the genus Homo outside Africa. Although the craniomandibular morphology of early Homo is well known as a result of finds from Dmanisi and African localities, data about its postcranial morphology are still relatively scarce. Here we describe newly excavated postcranial material from Dmanisi comprising a partial skeleton of an adolescent individual, associated with skull D2700/D2735, and the remains from three adult individuals. This material shows that the postcranial anatomy of the Dmanisi hominins has a surprising mosaic of primitive and derived features. The primitive features include a small body size, a low encephalization quotient and absence of humeral torsion; the derived features include modern-human-like body proportions and lower limb morphology indicative of the capability for long-distance travel. Thus, the earliest known hominins to have lived outside of Africa in the temperate zones of Eurasia did not yet display the full set of derived skeletal features.

——————–

—————————————————

“The Plio-Pleistocene site of Dmanisi, Georgia, has yielded a rich fossil and archaeological record documenting an early presence of the genus Homo outside Africa. Although the craniomandibular morphology of early Homo is well known as a result of finds from Dmanisi and African localities, data about its postcranial morphology are still relatively scarce. Here we describe newly excavated postcranial material from Dmanisi comprising a partial skeleton of an adolescent individual, associated with skull D2700/D2735, and the remains from three adult individuals. This material shows that the postcranial anatomy of the Dmanisi hominins has a surprising mosaic of primitive and derived features. The primitive features includea small body size, a low encephalization quotient and absence of humeral torsion; the derived features include modern-human-like body proportions and lower limb morphology indicative of the capability for long-distance travel. Thus, the earliest known hominins to have lived outside of Africa in the temperate zones of Eurasia did not yet display the full set of derived skeletal features.” “The inferred body mass of the large adult individual is between 47.6 kg and 50.0 kg. The body mass of the small adult individual is 40.2 kg. The body mass of the subadult is between 40.0 kg and 42.5 kg.” “Stature estimates for the subadult Dmanisi individual is between 144.9 cm and 161.4 cm. Stature estimates for the large adult individual is in a range of 146.6 cm – 166.2 cm.” (Lordkipanidze et al. 2007:S14).

Characterizing the Dmanisi hominids as small in size while narrating them is also evident in a ritual-like event with an international online audience, a TEDx talk in Tbilisi (2011), by David Lordkipanidze. In this narrative the focus is presenting the Dmanisi skull to giants of the human evolution scientific community from a small emerging country, during an international ritual-like gathering of scientists, a conference. Towards the end of his talk, at 12:09, he states that the Dmanisi hominid “was short” (compared to the then prevailing view about the size of the early Homo), “less than one meter fifty centimeters,” and an image of a Dmanisi skeleton is shown, and next to it it says “height 140-150 cm.” http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dC0gdpVS4uM Home georgionous – the first Europeans David’s article in out of Africa book – collection of articles Out of Africa because of “culture” (tools – ) David that Hominin the Dmanisi probably arrived in the region before the Dmanisi folks – based on their tools – based on their bodies, but based on primitive tools (like African) that were made by the so called small bodies But why call them out-of-Africa – if the tools and the fauna and flora that they lived in was similar to similar populations in the so-called (or now-called) Africa.

European Identity Debate: Professor David LORDKIPANIDZE What are the roots of European identity? What does European identity mean today and how is it related to European integration? How can the Council of Europe help foster positive European identities? The Debates on European Identity are an initiative of Thorbjørn Jagland, Secretary General of the Council of Europe, in response to the difficult and challenging times facing European societies today. They intend to discuss the current state of thinking and dynamics behind the concept of European Identity. They shoud serve as a catalyst of ideas and concepts for the future of Europe, thereby contributing to building constructive European identities. Co-organised by the Council of Europe and the Ecole Nationale d’Administration (ENA), the debates on European identity feature eminent personalities from politics, civil society and academic world. Each time, speakers address a different way the complexity of issues related to European identity.

European Identity Debate http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JLqIoKmcfhQ

—————————————-

Now let’s compare David Lordkipanidze’s remark (above) with that made by John Hawks, an American paleoanthropologist (U. of Wisconsin), who in his blog, linked below, states that” Dmanisi hominids were not short.”

http://johnhawks.net/weblog/fossils/lower/dmanisi/dmanisi_postcrania_nature_2007.html Hawks compares the Dmanisi hominids’ size with the data on size of contemporary foragers and of early Homo findings. Comparing the Dmanisi data with contemporary hunter-gatherer samples, Hawks confirms that the Dmanisi statures are typical of recent forager populations in terms of size. Hawks wonders why in the dominant narrative the Dmanisi individuals are small. He thinks that the real contrast is not between Dmanisi and living people, but between Dmanisi and the large East African “H. erectus” specimens. But he argues that “these large specimens are hardly typical in East Africa: they are the upper end of a range of variation in postcrania extending down to Lucy’s size, barely more than a meter tall. “We have often assumed that these larger specimens belong to H. erectus, but I think that the lower end of this range of variation is completely up for grabs.” Hawks discusses the reason for associating East African “Homo erectus” exclusively with the large-bodied specimens, it has to be with being able to go out of Africa. “It is another association, that of low sexual dimorphism and large body size, that is argued for a significant increase in home range size and dispersal potential in this species. I’ll call it the “long-legged colonists” hypothesis: the idea that hunter-gatherer ecology, large body size, and low sexual dimorphism were linked to each other, all enabling long-distance dispersal and the initial colonization of Eurasia.” “The Dmanisi body sizes refute this hypothesis. But looking back, the “long legged colonists” hypothesis was half incorrect chronology and half wishful thinking.” Hawks mentions the issue of size variability. “Were these early humans (Homo erectus) unusually variable in size? I don’t think so. If anything, they appear to have exhibited less variation in stature than human populations today. No ancient population was as tall as the Dutch. It is not even clear that early Pleistocene East Africans were as tall as recent East Africans, although they may have been so. No fossils yet assigned to Homo erectus were as short as Pygmies; although some Homo habilis-associated postcrania were even shorter. If the species boundaries are drawn right, there may be no problem of variability in the postcrania. That may be a big “if”. The limited degree of variation is fairly remarkable considering that the fossils in question span over a half-million years of time, in East Africa and Eurasia. Maybe there ought to be more variation than anyone is now assigning to H. erectus, and the species boundaries are wrong after all…” ——————– Small is beautiful, as it is usually said, but whether Dmanisi body sizes are small or average, Dmanisi is a beautiful place now, and I can imagine it was back then. Bodies intrigue us. They promise windows into the past that other archaeological finds cannot by bringing us literally face to face with history. Yet ‘the body’ is also highly contested. Archaeological bodies are studied through two contrasting perspectives that sit on different sides of a disciplinary divide. On one hand lie science-based osteoarchaeological approaches. On the other lie understandings derived from recent developments in social theory that increasingly view the body as a social construction. Through a close examination of disciplinary practice, Joanna Sofaer highlights the tensions and possibilities offered by one particular kind of archaeological body, the human skeleton, with particular regard to the study of gender and age. Using a range of examples, she argues for reassessment of the role of the skeletal body in archaeological practice, and develops a theoretical framework for bioarchaeology based on the materiality and historicity of human remains. 2009-2010 Skull 4 The Netherlands http://news.leiden.edu/news/world-famous-dmanisi-skull-to-leiden.html http://vimeo.com/7875027 http://www.cambridge.org/gb/knowledge/isbn/item1149509/?site_locale=en_GB

How should the institutional inheritance of national museums (purpose, culture, philosophy, etc.) shape their future role.

How do the historical narratives and material collections of national museums contribute to division and contestation? How do they, or might they, build bridges between nations and communities?

How have national museums been instrumentalised in government policy? How have they become socially active? How do national museums contribute to the values, perceptions and identities of citizens?

In a changing Europe, how can national museums contribute to greater social cohesion? How can the stories national museums tell and the treasures they display, be mobilised to build connections across Europe? ——-

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America

Earliest human occupations at Dmanisi (Georgian Caucasus) dated to 1.85–1.78 Ma

Reid Ferringa,1, Oriol Omsb, Jordi Agustíc, Francesco Bernad,2, Medea Nioradzee, Teona Sheliae, Martha Tappenf, Abesalom Vekuae, David Zhvaniae, and David Lordkipanidzee,1

Author Affiliations

Contributed by David Lordkipanidze, April 28, 2011 (sent for review February 27, 2011)

AbstractFull TextAuthors & InfoFiguresSIMetricsRelated ContentPDFPDF + SI

Next Section

Abstract

The early Pleistocene colonization of temperate Eurasia by Homo erectus was not only a significant biogeographic event but also a major evolutionary threshold. Dmanisi’s rich collection of hominin fossils, revealing a population that was small-brained with both primitive and derived skeletal traits, has been dated to the earliest Upper Matuyama chron (ca. 1.77 Ma). Here we present archaeological and geologic evidence that push back Dmanisi’s first occupations to shortly after 1.85 Ma and document repeated use of the site over the last half of the Olduvai subchron, 1.85–1.78 Ma. These discoveries show that the southern Caucasus was occupied repeatedly before Dmanisi’s hominin fossil assemblage accumulated, strengthening the probability that this was part of a core area for the colonization of Eurasia. The secure age for Dmanisi’s first occupations reveals that Eurasia was probably occupied before Homo erectus appears in the East African fossil record.

Lower Paleolithic paleoanthropology

In recent years, paleoanthropologists have intensified the search for evidence for one of the most significant events in human evolution: the dispersal of early Homo from Africa to Eurasia. That Homo erectus was the first hominin to leave Africa and colonize Eurasia has been accepted by paleoanthropologists for over a century. However, models that linked the first African exodus to increases in stature, encephalization, and technological advances (1⇓–3) have been challenged by discoveries at Dmanisi (4). Dmanisi is located in the southern Georgian Caucasus (41°20’10”N and 44°20’38”E), 55 km southwest of Tbilisi (Fig. 1). The prehistoric excavations at Dmanisi have been concentrated in the central part of a promontory that stands above the confluence of the Masavera and Pinasauri rivers. Lower Pleistocene deposits are preserved below the Medieval ruins and above the 1.85-Ma Masavera Basalt (Fig. 1). Those excavations yielded numerous exceptionally preserved hominin fossils. Stratigraphic studies revealed that that all of those hominin fossils are from sediments of stratum B, dated to ca. 1.77 Ma, based on 40Ar/39Ar dates, paleomagnetism, and paleontologic constraints (4, 5). In the main excavations, no artifacts or fossils have been found in the older stratum A deposits, which conformably overlie the Masavera Basalt. Dmanisi’s rich collection of hominin fossils reveals a population with short stature and cranial capacities of only 600–775 cc (4⇓⇓⇓⇓–9). Artifact assemblages are all indicative of a Mode I technology, with no bifacial tools (10). Recently completed testing in the M5 sector of Dmanisi has yielded in situ artifacts and faunal remains from the older stratum A deposits, pushing back Dmanisi’s occupational history into the upper Olduvai subchron. These findings indicate that African and Eurasian theaters for the evolution of early humans had been established even earlier than thought previously, with implications for the age of dispersals not only within Eurasia but also between Eurasia and Africa. This article describes the results of these investigations at Dmanisi and their implications for future research.

The latest

A Complete Skull from Dmanisi, Georgia, and the Evolutionary Biology of Early Homo

A Complete Skull from Dmanisi, Georgia, and the Evolutionary Biology of Early Homo

- David Lordkipanidze1,*,

- Marcia S. Ponce de León2,

- Ann Margvelashvili1,2,

- Yoel Rak3,

- G. Philip Rightmire4,

- Abesalom Vekua1,

- Christoph P. E. Zollikofer2,*

- 1Georgian National Museum, 3 Purtseladze Street, 0105 Tbilisi, Georgia.

- 2Anthropological Institute and Museum, Winterthurerstrasse 190, 8057 Zurich, Switzerland.

- 3Department of Anatomy and Anthropology, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, 69978, Israel.

- 4Department of Human Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA.

The site of Dmanisi, Georgia, has yielded an impressive sample of hominid cranial and postcranial remains, documenting the presence of Homo outside Africa around 1.8 million years ago. Here we report on a new cranium from Dmanisi (D4500) that, together with its mandible (D2600), represents the world’s first completely preserved adult hominid skull from the early Pleistocene. D4500/D2600 combines a small braincase (546 cubic centimeters) with a large prognathic face and exhibits close morphological affinities with the earliest known Homo fossils from Africa. The Dmanisi sample, which now comprises five crania, provides direct evidence for wide morphological variation within and among early Homo paleodemes. This implies the existence of a single evolving lineage of earlyHomo, with phylogeographic continuity across continents.http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/ngm/0208/feature1/assignment1.html ————————– CNN Fragments of humans’ ancient relatives are scattered across the globe. Sometimes a tooth or a few bones are all we have to tell us about an entire species closely related to humans that lived thousands or millions of years ago. So when anyone finds a complete skull of a possible human ancestor, paleoanthropologists rejoice. But with new knowledge comes new controversy over a fossil’s place in our species’ very fuzzy family tree. In the eastern European nation of Georgia, a group of researchers has excavated a 1.8 million-year-old skull of an ancient human relative, whose only name right now is Skull 5. They report their findings in the journal Science, and say it belongs to our genus, called Homo. “This is most complete early Homo skull ever found in the world,” said lead study author David Lordkipanidze, researcher at the Georgian National Museum in Tbilisi.

Skull 5 is the fifth example of a hominid — a bipedal primate mammal that walked upright — from this time period found at the site in Dmanisi, Georgia. Stone tools and animal bones have also been recovered from the area. The variation in physical features among the Dmanisi hominid specimens is comparable to the degree of diversity found in humans today, suggesting that they all belong to one species, Lordkipanidze said. But “if you will put separately all these five skulls and five jaws in different places, maybe people will call it as a different species,” he said. Now it gets more controversial: Lordkipanidze and colleagues also propose that these individuals are members of a single evolving Homo erectus species, examples of which have been found in Africa and Asia. The similarities between the new skull from Georgia and Homo erectus remains from Java, Indonesia, for example, may mean there was genetic “continuity across large geographic distances,” the study said. What’s more, the researchers suggest that the fossil record of what have been considered different Homo species from this time period — such as Homo ergaster, Homo rudolfensis and Homo habilis — could actually be variations on a single species, Homo erectus. That defies the current understanding of how early human relatives should be classified.

Because of Skull 5 and the other Dmanisi fossils, scientists are “rethinking what happened in Africa,” Lordkipanidze said. The Dmanisi individuals appear to have long legs and short arms, based on the fossils that have been found, said study co-author Marcia Ponce de Leon, of the Anthropological Institute at the University of Zurich, Switzerland, at a press conference. The braincase of Skull 5 is 546 cubic centimeters, which is smaller than expected. The biggest brain case found at Dmanisi is 75% larger than the smallest one, which is consistent with what is observed in modern humans, said study co-author Christoph Zollikofer of the Anthropological Institute in Zurich. At Dmanisi, researchers believe carnivores and hominids were fighting over animal carcasses. The stone tools appear to have been used in butchering, based on the cut marks on animal bones, Lordkipanidze said. They are comparable to tools that have been found in Africa. “It’s a real snapshot in time,” Lordkipanidze said of the Dmanisi site. Skull 5, excavated in 2005, was matched to a jaw discovered in 2000. The first example of a hominid fossil at Dmanisi was discovered in 1991. So what species came after Homo erectus in the history of human relatives? Scientists have no idea, Zollikofer said. “It would be nice to say this is the last common ancestor of Neanderthals and us, but we simply don’t know,” Zollikofer said. The Dmanisi fossils are a great find, say anthropology researchers not involved with the excavation. But they’re not sold on the idea that this is the same Homo erectus from both Africa and Asia — or that individual Homo species from this time period are really all one species. “The specimen is wonderful and an important contribution to the hominin record in a temporal period where there are woefully too few fossils,” said Lee Berger, paleoanthropologist at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, in an e-mail. But the suggestion that these fossils prove an evolving lineage of Homo erectus in Asia and Africa, Berger said, is “taking the available evidence too far.” Berger led the team that discovered Australopithecus sediba, a possible human ancestor that lived around 2 million years ago in South Africa. He criticized the authors of the new study for not comparing the fossils at Dmanisi to A. sediba or to more recent fossils found in East Africa. Ancient fossils question human family tree Lordkipanidze said he and colleagues consider A. sediba to be earlier and more primitive than the Dmanisi hominids, and that there’s “no doubt” the Georgian fossils belong to the Homo genus. But the selectivity of fossils compared to them in this study may have artificially biased the results toward the researchers’ hypotheses, Berger said. Ian Tattersall, curator emeritus at the American Museum of Natural History’s anthropology division, said in an e-mail that there’s “no way this extraordinarily important specimen is Homo erectus,” if theskull fragment discovered in Trinil, Java, Indonesia, defines the features of the Homo erectus group. The New York museum’s Hall of Human Origins takes visitors on a tour through human evolutionary history, showing distinct Homo species reflected in major fossil finds such as Turkana Boy (Homo ergaster) and Peking man (Homo erectus). ———————————————————————– The Dmanisi discovery may find a place there too, but it’s probably not going to result in relabeling other species, Tattersall said. “Right now I certainly wouldn’t change the Hall — except to add the specimen, which really is significant,” he said. There is an area of about 50,000 square meters at Dmanisi still to be excavated, so Skull 5 may have even more company.

—————–

Johanson on Dmanisi and Skull 5

PBS Newshour – Science

October 18, 2013 at 12:00 AM EST

http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/science/july-dec13/ancestry2_10-18.html

‘Mind-boggling’ skull discovery offers researchers a view into the ancient past

So, part of what makes this so exciting and unusual is just having a complete skull from that period, right?

DONALD JOHANSON, Arizona State University: Well, I think it’s absolutely mind-boggling. The preservation of this specimen from Georgia is extraordinary. It looks like something that you would find in a dissection room. It’s so complete. It’s got the lower jaw, the entire face, the complete brain case. It’s a view into the past into what our earliest ancestors in our own genus, Homo, looked like that none of us had anticipated.

JEFFREY BROWN: And then there’s the grouping of these remains at the site. Now, explain to us why this is important. DONALD JOHANSON: Well, at the site of Dmanisi, which is just about 20 kilometers north of Armenia in Georgia, there is a single geological layer, almost a snapshot in geological time, of a collection of bones, including five skulls. The most recent one announced, of course, is skull five, but also limb bones of the arms and legs and associated animal bones. And we know from the geological studies that this stratum samples a very, very thin period of time, maybe just over a few years. It was about 1.8 million years ago when probably saber-toothed cats killed and fed upon these early humans and dragged these skeletons into the cave, where they were preserved, they didn’t see light until 1.8 million years later.

JEFFREY BROWN: All right, so that grisly past gives us some interesting clues to what might have happened, though. So, to try to explain this in layman terms why this all interesting for the history of evolution, the thinking has been that there were various species, right, that some died out, some kept going through to our own, but that this at least raises the possibility that they were all part of one species?

DONALD JOHANSON: Well, I think it’s a little bit premature to include all of the specimens of our human genus, Homo, that have been found in Africa, that have been found in Asia, and now in Dmanisi, together in a single species. I think that the level of variation that we look at, the differences in the shape of the skull, and the face and the teeth and the jaws and so on, exceeds the definition of a single species. And, in Africa, it appears that we have several different species. So, this is not unusual for the evolution of a mammalian groups. All mammals undergo a certain degree of diversification. Darwin knew that. When he drew a family tree, it had many branches on it. This is one of those branches, but I think what we see in the variation in the African fossils is the presence of several different species.

JEFFREY BROWN: What is that the researchers at Dmanisi, at this site, what they saying that they see that suggests something a little more linear to them?

DONALD JOHANSON: Well, they see a clear connection, as we all do, between the Dmanisi fossils themselves in the shape of the face and the teeth and the jaws with fossils in Africa that reach back over two million years. So I think they see a lineage of Homo coming out of Africa. But I think there were other experiments in Africa that didn’t give rise to anything, that actually were extinct side branches. So what they see really is a direct connection between their fossils and a form or a species in Eastern Africa known as Homo ergaster, which means really the workman. And that was a species that we know goes back over two million years and probably was the progenitor for that lineage to that led out of Africa and is being picked up now in places like Dmanisi.

JEFFREY BROWN: And is it — this Dmanisi site, is it strange that a discovery — this discovery was made in what’s now Georgia on the Eurasian continent, rather than in Africa? Does it — what does it tell us about early ancestors, and does it change anything in our thinking about origins in Africa?

DONALD JOHANSON: Well, I think almost every time we hear about a new discovery of a human ancestor, it points to Africa. But here is a totally unanticipated place, between the Caspian Sea and the Black Sea, where hardly anybody ever thought of looking, except these Georgian scientists who were working there, and came up — have come up with discoveries that really revolutionize our ideas of when and why our ancestors left Africa. We used to think that we only got out of Africa maybe 500,000, maybe a million years ago. These are 1.8 million years old. We used to think that we didn’t get out of Africa until we had controlled fire, that we had sophisticated technology. There’s no evidence for fire at this site. They had very rudimentary, simple flake stone tools. This was man the explorer. This was part of what it means to be human, I think, that we are inquisitive, searching animals, and we are interested in knowing what’s beyond the next mountain, what’s around the next sand dune or whatever. And this is the first exploration of our genus outside of Africa, and that’s pretty mind-blowing. JEFFREY BROWN: And just briefly, just to — can you tell us what this creature, whatever it was, this skull, what would it have looked like and what would it have done?

DONALD JOHANSON: Well, I think that that’s part of the importance of having a series of five skulls. We know, for example, that there was differences — it was a significant difference in size. Males were much larger, more heavily built with thick browridges across the tops of their orbits, very heavy muscle insertions, probably around five-and-a-half, maybe six feet in stature, females someone shorter, much more lightly built, creatures that still had relatively small brains, but much bigger than the ape man fossils that we study in Africa, we call this tongue twister Australopithecus. But this was an advancement in evolutionary change. This was a time where we were undergoing a major transition from these more apelike creatures to more humanlike creatures. And the few features we see, like an increase in brain size, are very significant, because it means that these are creatures that were much more intelligent, that had a degree of inquisitiveness and ability that we have not anticipated.

JEFFREY BROWN: OK, a very exciting discovery, and much more work to come.

Donald Johanson at Arizona State University, thanks so much.

———–

Dmanisi Skull and Brand-New Caucasian Democracy

24 October, 2013

http://www.georgianjournal.ge/discover-georgia/25079-dmanisi-skull-and-brand-new-caucasian-democracy.html

Dr. Lorkipanidze later became the head of the Dmanisi research project and the National Museum.National Academy of Science, centers for kowledge production, in relation to nationalism.

The importance of the Dmanisi discoveries was that it went against the previous narratives with regards to time and place.

Scientists think that migration of the oldest man from Africa to Eurasia took place about one million years or relatively later – 600 000-800 000 thousand years ago. But the unique discovery in Dmanisi has shattered the basis of the firmly established hypothesis on the initial origin and settlement of human beings.

Academicians Leo Gabunia and David Lordkipanidze made a report on the results of investigations carried out by Georgian scientists on Dmanisi hominid and presented its mandible to the participants of an interna- tional symposium dedicated to the centenary of the discovery of the remains of the first Pithecanthropus (Island of Java, 1891). The well-preserved mandible, its primitive morphological features made a great impression on specialists and they unanimously recognized indisputable similarity of Dmanisi man with early hominids of Africa. Scientists commented widely on the Dmanisi discovery after the symposium. Discussion concerning Dmanisi man, its primitiveness and geological archaism has not stopped and is still going on in special publications. Some scientists challenged our assertion of the resemblance of Dmanisi and African hominids. The idea was launched that Dmanisi fossils were brought to the den by carnivores. That was a real fantasy, because its author was not aware of the site formation process in Dmanisi, besides carnivores, as saber-toothed cats could not bring their own skeletons to the den.

Shaking up evolutionary models

Shaking up evolutionary models